Designing for change in Łódź and beyond

In conversation with Edyta Skiba

I met Edyta Skiba at the Energy Regeneration of Cities Conference in Łódź, Poland. Prior to the conference Edyta had interviewed me for the Polish magazine Architektura & Biznes. It was clear that she had a depth of insights about the role of design in the world, which prompted me to turn the tables and conduct an interview with her.

Edyta’s work has three interconnected threads: she works as an architect, urbanist and journalist. She’s a practicing architect with BBGK Architekci studio in Warsaw, and is a PhD candidate at Łódź University of Technology where she is focusing on circular economies in peri-urban contexts (areas between urban and rural settings). For many years she has also conducted interviews for Architektura & Biznes. The main driver behind her work, Edyta says, is “curiosity, and the need for design to respond in a better way to the needs of society.”

One way in which the built environment is currently not responding to the needs of society, in Edyta’s view, is meeting “the basic need for humans to have a good, proper and safe space to live”, given the rapid increases in the cost of housing in Poland beyond. Another is addressing gender imbalances, responding to “the way women perceive the city and feel within the space. There are architectural and urban details that need to be solved, to provide safety for everyone.”

Edyta sees climate change and environmental impacts as a compelling reason to rethink the way in which the built environment is designed and financed, and to move towards circular business models that keep materials in use. She brings curiosity and engages with complexity in the work, as if design is a puzzle that endlessly renews itself.

“We need to ask many different questions about problems, building a wide mind-map of them, looking at them from different perspectives.”

This approach to design is refreshing in a world in which the default is often to grasp at solutions without a full picture of their consequences.

While now based in Warsaw, Edyta was brought up in Łódź and still has deep connections to the city. A textile manufacturing hub since the early nineteenth century, Łódź was thrown into economic decline and social disruption during the period after the fall of communism, when the region opened up to global supply chains. This had a major impact both on the physical built fabric and the social fabric of the city.

“The industry that provided the work for almost all the inhabitants wasn’t there anymore. The city was struggling with unemployment, with a workforce under-skilled for new conditions and trained for professions that were needed at the former factories. This is how we entered the age of capitalism, globalization and the internet.”

Łódź has been compared variously with Manchester during its nineteenth century manufacturing heyday, Detroit as it dealt with the loss of its major industry, and also Baltimore, given its “duopolis” relationship with a larger and dominant neighboring city (Warsaw, and Washington DC respectively).

The city is now forging a new path, building on its past, and looking to the future with energy transitions in mind. When I was in Łódź in 2023, demonstrable signs of regeneration were everywhere. These have included the “Mia100kamienic” initiative to renovate municipal-owned tenement buildings in different locations – an “acupuncture” approach as Edyta puts it - through which the city’s renovation of a building then inspires private owners to follow suit. Instead of selling off city-owned building stock, the city invested into public assets. A “lighthouse keepers” group of social workers worked to maintain close partnerships with the residents of buildings through the renovation process, to minimize displacement.

Incentives were provided to graduate students working in Łódź to rent apartments owned by the municipality, in order to keep young people in the city. Spaces for creative business were opened for lease to stimulate a student and creative economy. And the city established strong ties with the university, especially in terms of spatial planning processes and social revitalization programs.

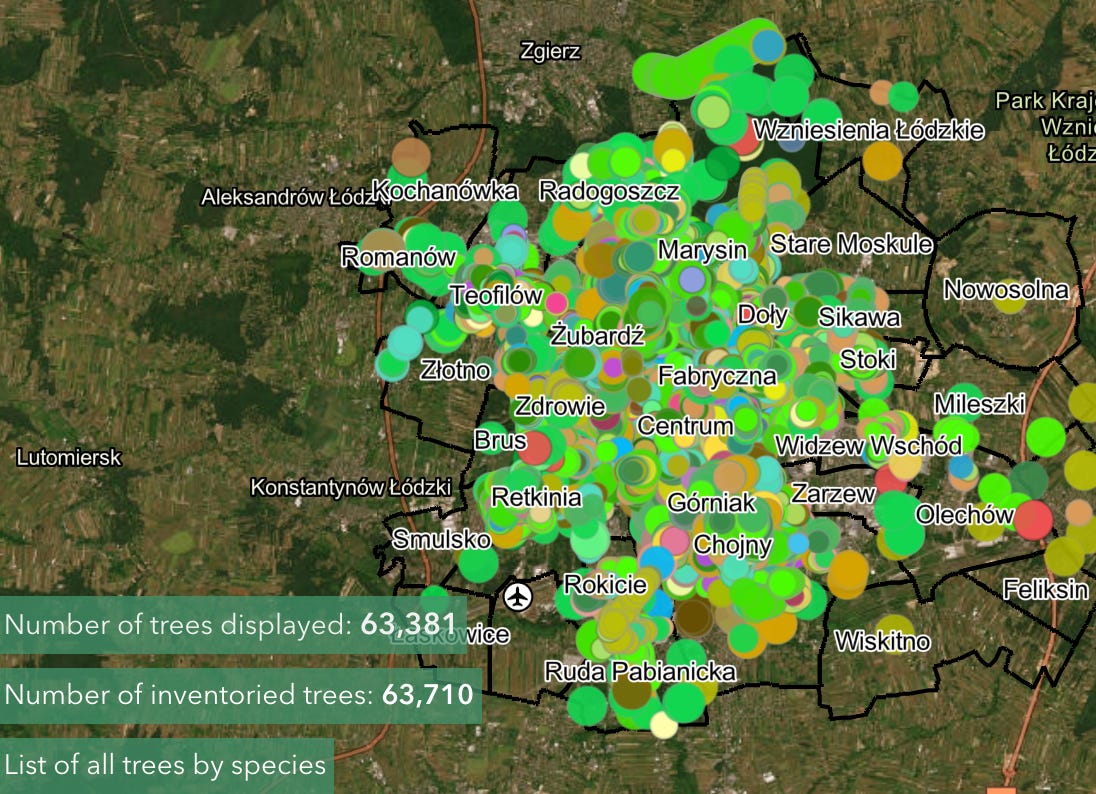

Łódź residents have also contributed to an inventory map of trees - Mapa Drzew Łodzi.

As the inventory website puts it [translated from Polish]:

“Let's assume that in Łódź there are about 400,000 trees growing on the streets and squares. Let's also assume that among the inhabitants of Łódź there are a thousand people who appreciate the value of trees and the role they play in the city, or simply like trees and care for them. This map is for you. Put on comfortable shoes, take your smartphone and a tape measure, and take an inventory of trees, even if only in your neighborhood.

These are our common trees. They will appear on the Tree Map of Łódź. Each tree will receive its own identification number and certificate. By visiting the website you will find out how many oaks, ginkgo trees and willows grow in Łódź. You will see where the largest trees in Łódź grow. You will find out what condition they are in. Maybe thanks to the map, when planning walks around the city, you will create your own trail of the most beautiful, oldest and most interesting trees in Łódź? Maybe thanks to the people involved in creating the map, we will discover previously unknown dendrological peculiarities?”

The city has also invested in start-up creative companies and in developing the city’s film industry: Łódź is home to Poland’s earliest film studios, to prominent directors, and to the animation company Semafor.

Edyta says:

“Not all of the initiatives have been 100% percent success stories. But I see that the city is really learning the lessons that it gains through the process. It’s growing in its knowledge. A lot of the initiatives have been done by building on and strengthening the local pride from the city's past, while also showing on the wider, national scale that it is a good place to visit. The investments that have been made into society and into the built environment are really visible.”

The approach seems to have public support - Łódź’ Mayor, Hanna Zdanowska, was re-elected for a third term this year.

Edyta works to bring a grounded, human dimension to design projects she works on in cities throughout Poland. Early in her career she was influenced by Jan Gehl’s “Cities for People” approach, and is motivated by “how you sense the urban space and perceive it, not only by the eyes, but also by your hearing, your feeling, by the many different senses.”

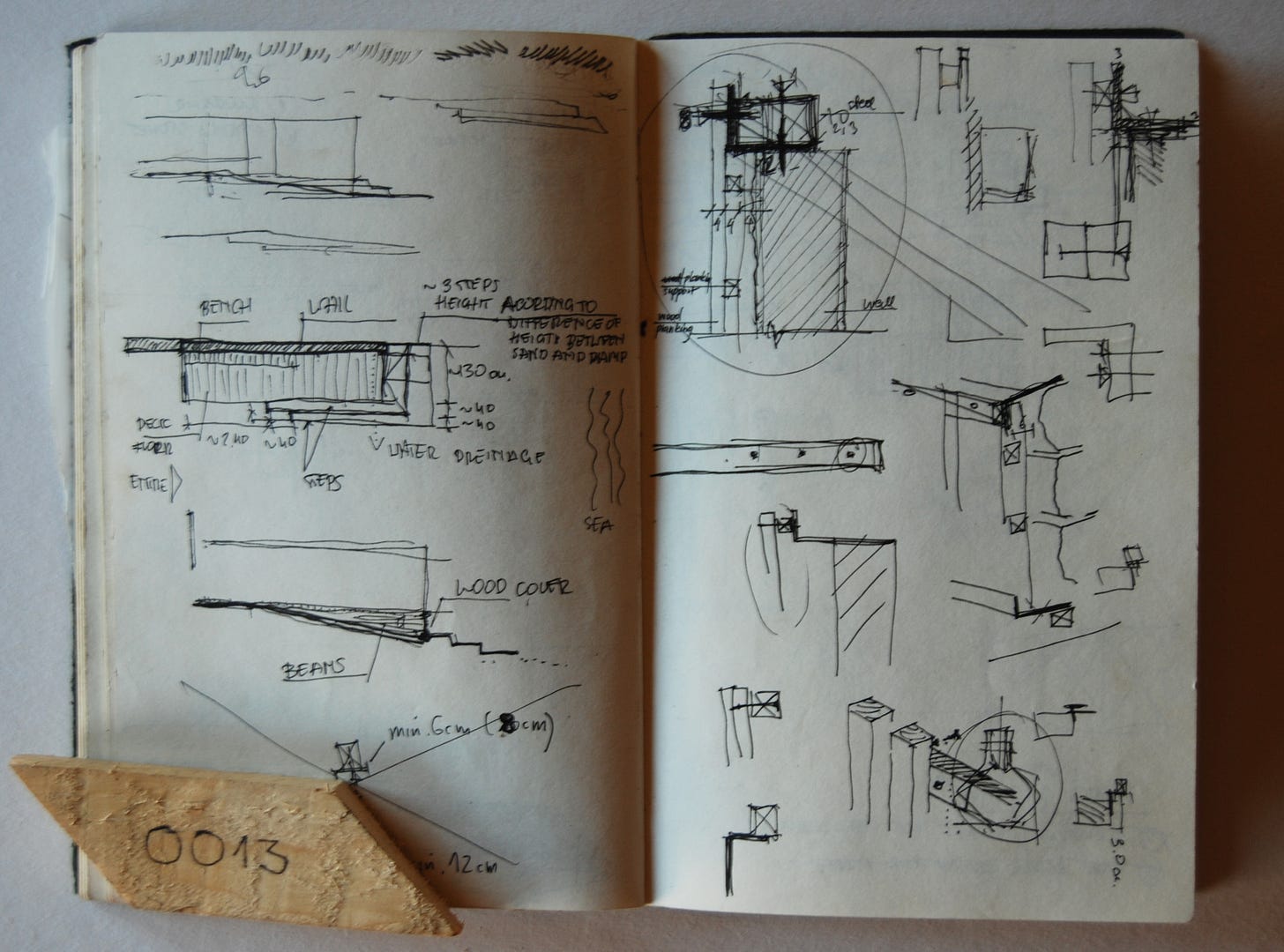

A project that has stayed with Edyta over the years is her participation in a MEDS workshop in Byblos, Lebanon. With her friend Karolina Turos-Wolny she co-led a team that worked with students from many regions on a design process using readily available materials to improve a remaining public entrance to a beach, along a strip of coastline where most beach access is private. Together they created a bench with a water connection, so bathers could wash before heading back into the city, and a guardian hut. Edyta was struck by the way in which beach-goers began interacting with, using, and appreciating the design before it was even finished.

While the building and design industries have been increasingly constrained by the narrow profit-generating demands of the market, there is a growing movement underway to broaden the lens and redefine concepts of value. Edyta’s current practice BBGK Architekci aims to incorporate dimensions such as diversity, city-making, community, environment and mobility through its projects. The office enters into discussions with clients on ways to distribute project budgets in ways that take those dimensions into account.

“When I was starting to work as a professional architect, the idea of human scale architecture was only starting to grow. Now it is becoming more like a standard. It is also thanks to the consciousness in society about architecture, urban design, about ways in which a city can look like. We are also more aware of the negative examples of urban design and their impacts in people’s lives.”

Edyta would like to also see a shift in value reflected in the architectural profession itself. She cites an exhibition by Czechia at the Venice biennale, which asked, “how can architects design a better world if they themselves work in a ‘toxic’ work environment?”. There is growing recognition that the mainstream business of architecture is structured in a way that stands in the way of architecture’s potential to transform places for the better.

Curiosity expands the space for what’s possible. Edyta says: “It’s a question of asking yourself while you design even just one small element, simple questions such as why? What's the purpose? What for? For whom? Each element of a space is interlinked.”

**************************

More on Łódź, its past, and transitions underway:

On the May Day 1892 Łódź uprising, one of the first general strikes in the Russian empire

Looking back to the period of WW2, when Jews and Roma were segregated into the Łódź ghetto, and many sent to concentration camps

ICLEI’s “member in the spotlight” on Łódź, on its environmental initiatives

The ReHousin initaitive: University of Łódź is a partner together with universities in eight other European cities in this multi-year project exploring the impacts of the region’s green and digital transitions on housing inequalities

And - expanding to a global lens - Edyta’s interview with me in Architektura & Biznes, on human rights and the built environment lifecycle